1. Sharanjit Padda, age 26, London.

“I was born here. I’m a true Londoner. I’ve always felt welcomed—if anything, I think my cultural heritage has earned me more respect,” says schoolteacher Sharanjit Padda. She wants immigrants to be accepted but also to accept British culture: “It’s a give-and-take.” Robin Hammond / National Geographic

Where did the project begin for you and in what way was this a personal endeavor?

RH: I’ve lived pretty much all my adult life away from my homeland, mostly in Europe. I’m acutely aware of the discussions we’re having about immigrants on the continent; when I hear politicians talking about immigration, they’re also talking about me. But my experience couldn’t be more different than that of Syrians coming here today. There is no single immigrant experience.

When I first moved to the United Kingdom 15 years ago, I was doing a lot of stories about immigration in the north of the country, and sometimes I would cover rallies of the British National Party (an anti-immigration party.) People at those rallies would complain to me about the immigrants in their communities, not understanding, of course, that I was an immigrant as well.

While I was very aware of being an immigrant, I think sometimes to the natives of European countries, I’m perceived differently to the immigrants we generally talk about in the media. I’m white and speak English — I look and sound more or less like the native population. I began to understand that there’s often a strong cultural and racial aspect to the anti-immigrant point of view.

What was one thing you took away from this body of work that was entirely unexpected?

RH: We did this work with five different immigrant populations, and I expected a large amount of diversity between those groups, like the Turks, Algerians, and the Syrians. What I didn’t quite expect was the massive diversity within those groups, and it just reaffirmed to me that we’re all just individuals and sometimes what brings us together or separates us is not necessarily about geography or culture. There are many things that influence who we are or our identity. Using the name of a country as their only defining feature is simplistic. There are things that provide a stronger identity for many people than the place they were born.

What do you hope people will take away from these images?

RH: That fundamentally we are all just people trying to get on. That people are people are people. I think that people are afraid most of what they don’t know, and I hope that by hearing these stories, people will realize that the things that are common between us are stronger than those that divide us. I think it’s human instinct to seek out how we are different, but I hope people will see that we are all fundamentally the same in our grand design, in our hopes and dreams.

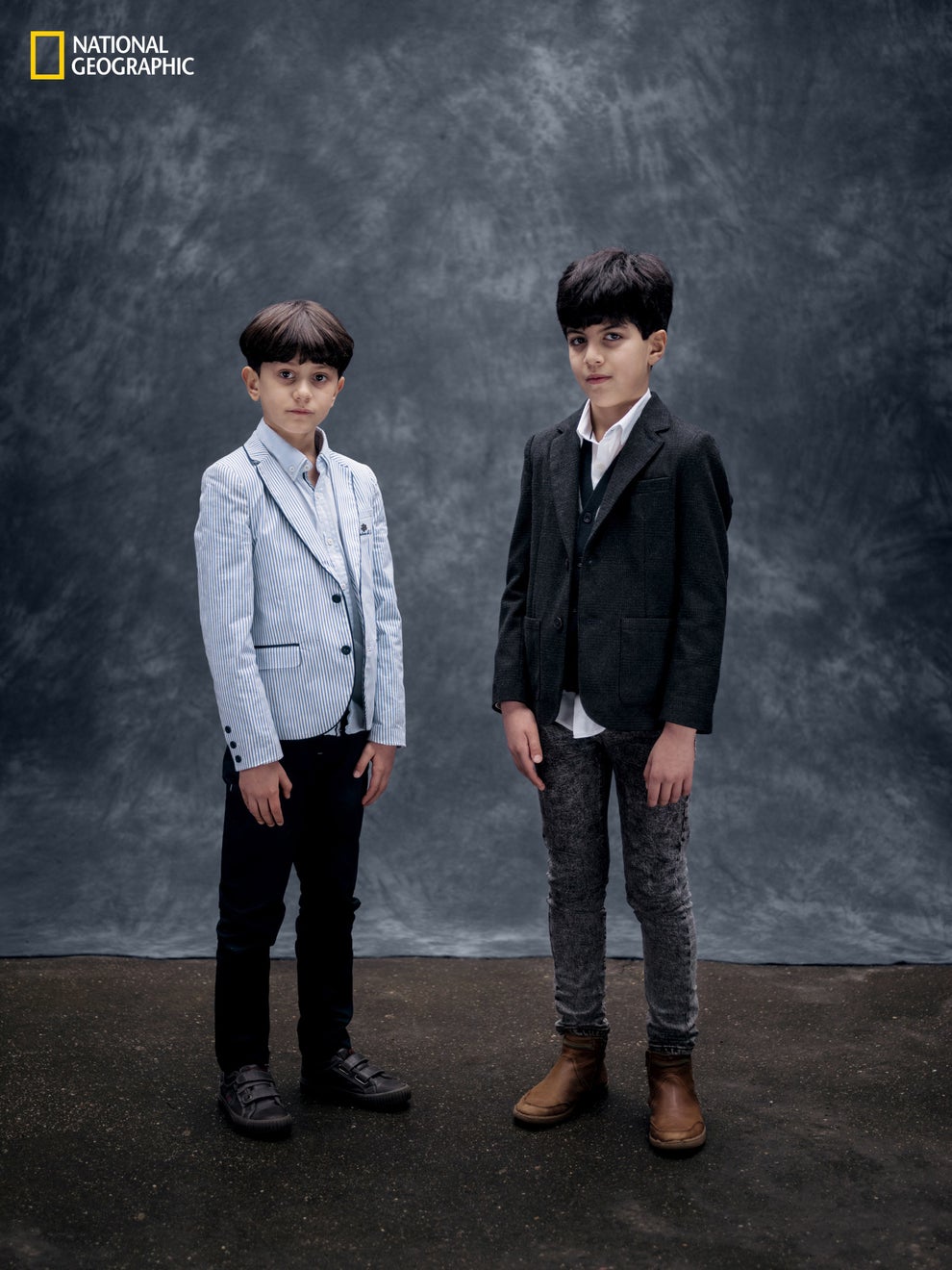

2. Ilyas (left) and Massyle Mouzaoui, ages 8 and10, Paris.

“I feel I can be 100 percent French and 100 percent Algerian,” says Massyle Mouzaoui (right). His brother Ilyas agrees. They live in a comfortable Paris suburb with their French mother and their father, an Algerian naturalized in France, who says he’s now helping “to build this country.” Robin Hammond / National Geographic

3. Asad Abdiassiz Dahir, age 16, Sweden.

“I see myself as a Somali and think I will always be a Somali. I came to Sweden to find peace. Sweden is a very good country,” says Asad Abdiassiz Dahir. In Mogadishu he was under pressure to join the militant Islamist group al Shabaab—so he fled. His family is still in Somalia. Robin Hammond / National Geographic

4. The Tecimen family, Germany.

“We live here, we were born here, we have grown up here. But the place I feel in my heart is Turkey,” says Ali Tecimen, 34 (back row, blue jacket). His grandparents (front) came to Germany in the 1970s as guest workers, when his mother (right) was a child. The family, including Tecimen’s wife (left) and two children, lives in Berlin. Robin Hammond / National Geographic

5. Isra Ali Saalad, age 10, Sweden.

In May 2015, 10-year-old Isra Ali Saalad came to Malmö from Mogadishu with her mother and two siblings. “The reason we came to this country is because it is safe,” says her sister, Samsam, 19. Samsam’s experience of Sweden has been all good, “only I’ve fallen short in learning the language.” Robin Hammond / National Geographic

6. Nichattar Pal, age 92, London.

“I came here because my Sardarji came from India, to get an education for our children,” says 92-year-old Nichattar Pal, speaking of her husband. Since she arrived in 1970, her London family has grown to include two generations. “I am happy here, very happy.” Robin Hammond / National Geographic

7. Ikram Chahmi Gheidene, age 23, Paris.

“I don’t wear my veil all the time. I put it on when I leave the university and go to the mosque,” says Ikram Chahmi Gheidene. Fleeing terrorism, her family came to Paris when she was eight. She feels at home and safe—but also wary, as suspicion of immigrants rises. Robin Hammond / National Geographic

8. Akram Koujer, age 53, Germany.

“The people here live in real freedom, and I can see that, and I am happy for them,” says Akram Koujer about Germany. Koujer, an ethnic Kurd, left his home and his jeans factory in Syria because “my family and I were threatened. My son was a soldier, so he needed to kill or be killed.” Robin Hammond / National Geographic

9. Mohamed Ali Osman, age 32, Sweden.

“One reason why I like this country is the hospitality. They welcome the refugees with open arms,” says Mohamed Ali Osman, who joined his wife in Sweden in 2012. But, he adds, “in this country it is hard not having a job, and the main reason why this happens is language barriers.” Robin Hammond / National Geographic

10. Khader family, Germany.

“We are doing fine here, and we were well received,” says Abed Mohammed Al Khader, 88, patriarch of a family of 16 that fled Syria two years ago, but “we want to go back.” This past February they arrived in Berlin and were given shelter, with 1,500 other refugees, in a large gymnasium near the Olympic stadium. Robin Hammond / National Geographic

11. Ipek Ipekcioglu, Germany.

“I feel Turkish and German and a human being and a lesbian. I have many cultures in me,” says DJ Ipek Ipekcioglu, who grew up in Berlin and lives there today. Germany still has trouble accepting the children and grand children of Turkish guest workers, she says: “We’re working on it.” Robin Hammond / National Geographic

12. Patricia Fatima Houiche, age 66, France.

“The discrimination started at school; I was six or seven. It was during the Algerian war,” says writer Patricia Fatima Houiche. Her mother was French, her father (photograph) an Algerian independence leader. She has lived most of her life in France. Her children are there too. But she hopes to be buried in Algeria. Robin Hammond / National Geographic